In recent weeks, two of the oldest issues on the internet have reared their ugly heads again: the demand that people use their ‘real names’ on social media, and the suggestion that we should undermine or ban the use of encryption – in particular end-to-end encryption. As has so often been the case, the argument has been made that we need to do this to ‘protect’ children. ‘Won’t someone think of the children’ has been a regular cry from people seeking to ‘rein in’ the internet for decades – this is the latest manifestation of something with which those concerned with internet governance are very familiar.

Superficially, both these ideas are attractive. If we force people to use their real names, bullies and paedophiles will be easier to catch, and trolls won’t dare do their trolling – for shame, perhaps, or because it’s only the mask of anonymity that gives them the courage to be bad. Similarly, if we ban encryption we’ll be able to catch the bullies and paedophiles, as the police will be able to see their messages, the social media companies will be able to algorithmically trawl through kids’ feeds and see if they’re being targeted and so forth. That, however, is very much only the superficial view. In reality, forcing real names and banning or restricting end-to-end encryption will make everyone less safe and secure, but will be particularly damaging for kids. For a whole series of reasons, kids benefit from both anonymity and encryption. Indeed, it can be argued that they need to have both anonymity and encryption available to them. A real ‘duty of care’ – as suggested by the Online Safety Bill – should mean that all social media systems implement end-to-end encryption for its messaging and make anonymity and pseudonymity easily available for all.

Children need anonymity

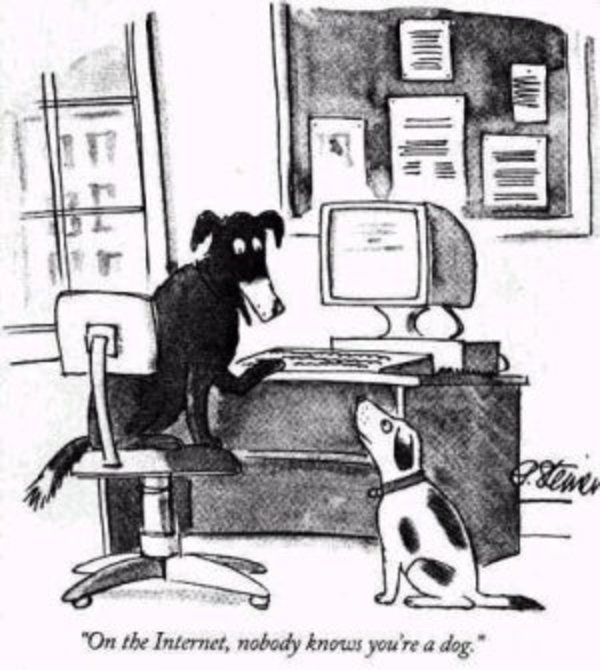

The issues surrounding anonymity on the internet have a long history – Pete Steiner’s seminal cartoon ‘On the Internet, Nobody Knows You’re a Dog’ was in the New Yorker in 1993, before social media in its current form was even conceived: Mark Zuckerberg was 9 years old.

It’s barely true these days – indeed, very much the reverse a lot of the time, as the profiling and targeting systems of the social media and advertising companies often mean they know more about us that we know ourselves – but it makes a key point about anonymity on the net. It can allow people to at least hide some things about themselves.

This is seen by many as a bad thing – but for children, particularly children who are the victims of bullies and worse, it’s a critical protector. As those who bully kids are often those who know the kids – from school, for example – being forced to use your real name means leaving yourself exposed to exactly those bullies. Real names becomes a tool for bullies online – and will force victims either to accept the bullying or avoid using the internet. This, of course, is not just true for bullies, but for overbearing parents, sadistic teachers and much worse. It is really important not to just think about good parents and protective teachers. For the vulnerable children, parents and teachers can be exactly the people they need to avoid – and there’s a good reason for that, as we shall see.

Some of those who had advocated for real names have recognised this negative impact, and instead suggest a system like ‘verified IDs’. That is, people don’t have to use their real names, but in order to use social media they need to prove to the social media company who they are – providing some kind of ID verification documentation (passports, even birth certificates etc) – but can then use a pseudonym. This might help a little – but has another fundamental flaw. The information that is gathered – the ID data – will be a honeypot of critically important and dangerous data, both a target for hackers and a temptation for the social media companies to use for other purposes – profiling and targeting in particular. Being able to access this kind of information about kids in particular is critically dangerous. Hacking and selling such information to child abusers in particular isn’t just a risk, it is pretty much inevitable. The only way to safeguard this kind of data is not to gather it at all, let alone put it in a database that might as well have the words ‘hack me’ written in red letters a hundred feet tall.

Children need encryption

Encryption is a vital protection for almost everything we do that really matters on the internet. It’s what makes online banking even possible, for example. This is just as true for kids as it is for adults – indeed, in some particular ways it is even more true for kids. End-to-end encryption is especially important – that is, the kind of encryption that means on the sender and recipient of a message can read it, not even the service that the message is sent on.

The example that Priti Patel and others are fighting in particular is the implementation of end-to-end encryption across all Facebook’s messaging system – it already exists on WhatsApp. End-to-end encryption would mean that not even Facebook could read the messages sent over the system. The opposers of the idea think it means that they won’t be able to find out when bullies, paedophiles etc are communicating with kids – bullying or grooming for example – but that misses a key part of the problem. Encryption doesn’t just protected ‘bad guys’, it protect everyone. Breaking encryption doesn’t just give a way in for the police and other authorities, it gives a way in for everyone. It removes the protection that the kids have from those who might target them.

End-to-end encryption protects against one other group that can and does pose a very significant risk to kids: the social media companies themselves. It should be remembered that the profiling and targeting of kids that is done by the social media companies is itself a significant danger to kids. In 2017, for example, a leaked document revealed that Facebook in Australia was offering advertisers (and hence not just advertisers) the opportunity to target vulnerable teens in real time.

“…By monitoring posts, pictures, interactions and internet activity in real-time, Facebook can work out when young people feel “stressed”, “defeated”, “overwhelmed”, “anxious”, “nervous”, “stupid”, “silly”, “useless”, and a “failure”,”

Facebook, of course, backed off from this particular programme when it was revealed – but it should not be seen as an anomaly but as part of the way that this kind of system works, and of the harm that the social media services themselves can represent for kids. End-to-end encryption to begin to limit this kind of thing – only to a certain extent, as the profiling and targeting mechanisms work on much more than just the content of messages. It could be a start though, and as kids move towards more private messaging systems the capabilities of this kind of hard could be reduced. If more secure, private and encrypted systems become the norm, children in particular will be safer and more secure

Children need privacy

The reason that kids need anonymity and encryption is a fundamental one. It’s because they need privacy, and in the current state of the internet anonymity and encryption are key protectors of privacy. More fundamentally than that, we need to remember that everyone needs privacy. This is especially true for children – because privacy is about power. We need privacy from those who have power over us – an employee needs privacy from their employer, a citizen from their government, everyone needs privacy from criminals, terrorists and so forth. For children this is especially intense, because so many kinds of people have power over children. By their nature, they’re more vulnerable – which is why we have the instinct to wish to protect them. We need to understand, though, what that protection could and should really mean.

As noted at the start, ‘won’t someone think of the children‘ has been a regular mantra – but it only gives one small side of the story. We need not just to think of the children, but think like the children and think with the children. Move more to thinking from their perspective, and not just treat them as though they need to be wrapped in cotton wool and watched like hawks. We also need to prepare them for adulthood – which means instilling in them good practices and arming them with the skills they need for the future. That means anonymity and encryption too.

Duty of care?

Priti Patel has suggested the duty of care could mean no end-to-end encryption, and Dowden has suggested everyone should have verified ID. There’s a stronger argument in both cases precisely the opposite way around – that a duty of care should mean that end-to-end encryption is mandatory on all messenger apps and messaging systems within social networking services, and that real names mandates should not be allowed on social networking systems. If we really have a duty of care to our kids, that’s what we should do.

Paul Bernal is Professor of Information Technology Law at UEA Law School