Category: Parenting

Children have a right to privacy

The latest proposal from David Cameron’s ‘Advisor on Childhood’, Claire Perry, is that parents should ‘snoop’ on their children’s texts. Apparently it’s ‘bizarre that parents treat youngsters’ internet and mobile exchanges as private’, as reported in the Daily Mail.

For those of us who work in the privacy field – and indeed for anyone who works or has knowledge of children’s rights – it’s Claire Perry’s ideas that are bizarre. In fact, I’d go a lot further: to anyone who pays any real attention to their children, that kind of idea should be bizarre. Children have a right to privacy – and not in the technical, legal sense (though in that too, because it’s enshrined in Article 16 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which the UK has both signed and ratified) but in what I would call the real, natural, sense. They want privacy. They need privacy. They demand privacy. Anyone who has children, who spends time with and listens to their children, who respects their children should be able to see that.

Part of that privacy – perhaps the most important part of that privacy – relates to privacy from their parents. That’s the part that children are most likely to care about too – they’re not so worried about the government snooping on them, or companies gathering their personal details for marketing purposes – but they do care about, and need to have some control over, what their parents know about their private thoughts. And we, as parents, need to understand that and respect that – if we are to understand and respect our children. If you want to know what your child is thinking about and caring about, and what they might be doing in their private lives, the best way, as the excellent @SturdyAlex tweeted this morning, is to ‘foster a relationship with them where they trust you enough to tell you’.

Of course the extent to which this is true varies from child to child and from age to age, but children all want and need privacy, and if we don’t understand and respect that all we’ll do is make them less likely to respect and to trust us – and hence more likely to find ways to hide the stuff that really matters from us.

So, Mr Cameron, and Ms Perry, don’t snoop on your children’s texts – or encourage anyone else to. Encourage them to listen to their children more, to respect their children more, to build better relationships to their children. Help your children to help themselves…

It’s about the children…

The Jimmy Savile story has provoked a huge amount of reaction – revulsion, disgust, anger, frustration, and great many attempts to find someone or something to blame. One of the biggest questions being asked is why we didn’t find out about it earlier – so many people seem to have known about it, or at least suspected what was happening, so why didn’t the news come out?

Many different suggestions have been made. Some blame the BBC – and its failures as an institution over this and related matters are all too clear. Some have blamed the libel laws – saying that they would have told the story if it hadn’t been for the threat of a big law suit. For me (as someone who teaches defamation law) that one really doesn’t wash: it may have made a small difference, but newspapers and others have published many, many stories over the years with far less evidence and with pretty much a guarantee of legal action. If they really wanted to publish, they would have.

Some of the ‘mea culpa’ stories from celebrities and others who knew but said nothing have rung true – but others haven’t. For many of them, if they’d really wanted to, they could have said something. For some it might have been ‘career suicide’ to do so – but is your career worth so much? Is anything worth so much?

That, brings me to my point. The main reason, as I see it, that the information didn’t get out, it ultimately that we didn’t care enough. Why? Well, there are two closely connected issues. Firstly, the idea of a man having sex with a young girl wasn’t (and still isn’t) considered such a bad thing. Rock-stars and underage groupies wasn’t (and still isn’t) seen as child abuse by a large number of people. The opposite. It’s almost one of the perks of the job. That’s not just a 70s attitude, it’s a current one. If you look back at the story of the 15 year old girl who went off to France with her 30s teacher, some of the reactions – indeed some of the press coverage – made that very clear. ‘Lucky bloke’ was how it was described by some. The story was presented to a great extent as titillating, a bit scandalous, not as what it was. For many men, the idea of a good-looking and ‘mature’ 15 year old girl seemed very attractive – and if you look at (for example) the sidebar on the Mail Online you can see that idea repeated again and again and again.

The second point, though it might not seem so obvious, is closely related: our overall attitude to young people. We don’t respect them – and we don’t take them seriously. We don’t listen to them, and we don’t believe them – and they know it. We laugh at their taste in music (Justin Bieber, One Direction etc) and their taste in clothes – or we demonise them as terrifying youths in hoodies. What we don’t do is treat them with respect, and try to properly listen to them or be willing to take seriously what they take seriously. To some parents – at least as it’s presented in the media – children are possessions or investments, or devices to be controlled. To some people children are something to be ‘managed’, or corralled like cattle – stop them gathering on street corners, ban them from places. The whole ASBO approach to children took this angle. Does it help? Only at the most superficial level – and it spreads a culture that says that children and young people aren’t worth listening to. They’re a problem to be managed.

So of course it’s hard for children to speak up when things really matter. If they’re not used to being listened to or taken seriously, they won’t talk. If they’re used to their wishes and ideas being either derided or over-riden, why would they think it was worth trying to be heard?

Of course what Savile did was hideously monstrous, and I doubt very much that many of those who knew or had suspicions over Savile and didn’t speak up knew that much of it – but the many who knew a little and didn’t speak up either knew they wouldn’t be listened to, or didn’t think it was such a big deal. Given our attitudes to children in other ways, the more ‘obvious’ stuff he did – groping a few teenaged girls on TV or in his caravan – wouldn’t have been seen as such a big deal. That attitude wasn’t (and isn’t) restricted to a few institutions or a few people – it pervaded (and to an extent still pervades) pretty much our whole society.

That’s not say things aren’t getting better – I think they are, but not to the extent that some people seem to think. Until we show more respect to children, until we listen more to children, until we trust our children a lot more, things won’t change nearly enough…

Will the government ‘get’ digital policy?

I had an interesting time at the ‘Seventh Annual Parliament and Internet Conference’ yesterday – and came away slightly less depressed than I expected to be. It seemed to me that there were chinks of light emerging amidst the usually stygian darkness that is UK government digital policy and practice – and signs that at least some of the parliamentarians are starting to ‘get it’. There were also some excellent people there from other areas – from industry, from civil society, from academia – and I learned as much from private conversations as I did in the main sessions.

The highlight of the conference, without a doubt, was Andy Smith, the PSTSA Security Manager at the Cabinet Office, recommending to everyone that they should use fake names on the internet everywhere except when dealing with the government – the faces of the delegation from Facebook, whose ‘real names’ policy I’ve blogged about before were a sight to behold. Andy Smith’s suggestion was noted and reported on by Brian Wheeler of the BBC within minutes, and made Slashdot shortly after.

It was a moment of high comedy – Facebook’s Simon Milner, on a panel in the afternoon, said he had had a ‘chat’ with Andy Smith afterwards, a chat which I think a lot of us would have liked to listen in on. The comedic side, though, reveals exactly why this is such a thorny issue. Smith, to a great extent, is right that we should be deeply concerned by the extent to which our real information is being gathered, held and used by commercial providers for their own purposes – but he’s quite wrong that we should be able and willing to trust the government to hold our data any more securely or use it any more responsibly. The data disasters when HMRC lost the Child Benefit details of 25 million families or the numerous times the MoD has lost unencrypted laptops with all the details of both serving and retired members of the armed forces – and potential recruits – are not exceptions but symptoms of a much deeper problem. Trusting the government to look after our data is almost as dangerous as trusting the likes of Facebook and Google.

The worst aspect of the conference for me was that there seemed to still be a large number of people who believed that ‘complete’ security was not just possible but practical and just a few tweaks away. It’s a dangerous delusion – and means that bad decisions are being made, and likely to continue. A few other key points of the conference:

- Chloe Smith, giving the morning keynote, demonstrated that she’d learned a little from her Newsnight mauling – she was better at evading questions, even if she was no better at actually answering them.

- In Chi Onwurah, Labour have a real star – I hope she gets a key position in a future Labour government (should one come to pass)

- We’ve got a long way to go with the Defamation Bill – without seeing the regulations that will accompany the bill, which apparently haven’t even been drafted yet, it’s all but impossible to know whether it will have any real effect (at least insofar as the internet is concerned)

- In a private conversation, someone who really would know told me that one of the problems with sorting out the Defamation Bill has been an apparent obsession that Westminster insiders have with the ‘threat’ from anonymous bloggers – I suspect Guido Fawkes would be delighted by the amount of fear and loathing he seems to have generated in MPs, and how much it seems to have distracted them from doing what they should on defamation and libel reform.

- After a few conversations, I’m quietly optimistic that we’ll be able to defeat the Communications Data Bill – it wasn’t on the agenda at the conference, but it was on many people’s minds and the whispers were generally more positive than I had feared they might be. Time will tell, of course.

- Ed Vaizey is funny and interesting – but potentially deeply dangerous. His enthusiasm for the ‘iron fist’ side of copyright enforcement built into the Digital Economy Act was palpable and depressing. The way he spoke, it seemed as though the copyright lobby have him in the palm of their hand – and that neither they nor he have learned anything about the failure of the whole approach.

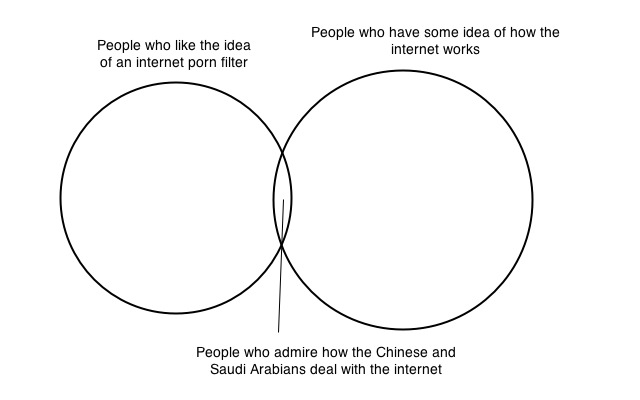

- Vaizey’s words on porn-blocking – he seemed to suggest that we’ll go for an ‘opt-out’ blocking systems, where child-free households would effectively have to ‘register’ for access to porn, something which has HUGE risks (see my blog here) – were worrying, but again, another insider assured me that this wasn’t what he meant to say, nor the proposal currently on the table. This will need very careful watching!!

- The savaging of Vaizey by a questioner from the floor revealing how much better and cheaper broadband internet access was in Bucharest than in Westminster was enjoyed by most – but not Vaizey, nor the industry representatives who remained conspicuously quiet.

- Julian Huppert – my MP, amongst other things – was again impressive, and seems to have understood the importance of privacy in all areas: the fact that Nick Pickles of Big Brother Watch was invited to the panel on the internet of things that Huppert chaired made that point.

- On that subject – mentions of either privacy or free speech were conspicuous by their absence in the early sessions on cybersecurity, but they grew both in presence and importance during the day. I asked a couple of questions, and they were both taken seriously and answered reasonably well. There’s a huge way to go, of course, but I did feel that the issue is taken a touch more seriously than it used to be. Mind you, none of the government representatives mentioned either in their speeches at all – it was all ‘economy’ and ‘security’, without much space for human rights….

- The revelation from the excellent Tom Scott that though the rest of us are blocked from accessing the Pirate Bay, it IS accessible from Parliament was particularly good – and when my neighbour accessed the site and saw the picture of Richard O’Dwyer on the front page, it was poignant…

I came away from the conference with distinctly mixed feelings – there are some very good signs and some very bad ones. The biggest problem is that the really good people are still not in the positions of power, or seemingly being listened to – and those at the top don’t seem to be changing as fast as the rest. If we could replace Ed Vaizey with Julian Huppert and Chloe Smith with Chi Onwurah, government digital policy would be vastly improved….

The myth of technological ‘solutions’

A story on the BBC webpages caught my eye this morning: ‘the parcel conundrum‘. It described a scenario that must be familiar to almost everyone in the UK: you order something on the internet and then the delivery people mess up the delivery and all you end up with is a little note on the floor saying they tried to deliver it. Frustration, anger and disappointment ensue…

…so what is the ‘solution’? Well, if you read the article, we’re going to solve the problems with technology! The new, whizz-bang solutions are going to not just track the parcels, but track us, so they can find us and deliver the parcel direct to us, not to our unoccupied homes. They’re going to use information from social networking sites to discover where we are, and when they find us they’re going to use facial recognition software to ensure they deliver to the right person. Hurrah! No more problems! All our deliveries will be made on time, with no problems at all. All we have to do is let delivery companies know exactly where we are at all times, and give them our facial biometrics so they can be certain we are who we are.

Errr… could privacy be an issue here?

I was glad to see that the BBC did at least mention privacy in passing in their piece – even if they did gloss over it pretty quickly – but there are just one or two privacy problems here. I’ve blogged before about the issues relating to geo-location (here) but remember delivery companies often give 12 hour ‘windows’ for a delivery – so you’d have to let yourself be tracked for a long time to get the delivery. And your facial biometrics – will they really hold the information securely? Delete it when you’re found? Delivery companies aren’t likely to be the most secure or even skilled of operators (!) and their employees won’t always be exactly au fait with data protection etc – let alone have been CRB checked. It would be bad enough to allow the police or other authorities track us – but effectively unregulated businesses to do so? It doesn’t seem very sensible, to say the least…

…and of course under the terms of the Communications Data Bill (of which more below) putting all of this on the Internet will automatically mean it is gathered and retained for the use of the authorities, creating another dimension of vulnerability…

Technological solutions…

There is, however, a deeper problem here: a tendency to believe that a technological solution is available to a non-technological problem. In this case, the problem is that some delivery companies are just not very good – it may be commercial pressures, it may be bad management policies, it may be that they don’t train their employees well enough, it may be that they simply haven’t thought through the problems from the perspective of those of us waiting for deliveries. They can, however, ‘solve’ these problems just by doing their jobs better. A good delivery person is creative and intelligent, they know their ‘patch’ and find solutions when people aren’t in. They are organised enough to be able to predict their delivery times better. And so on. All the tracking technology and facial recognition software in the world won’t make up for poor organisation and incompetent management…

…and yet it’s far too easy just to say ‘here’s some great technology, all your problems will be solved’.

We do it again and again. We think the best new digital cameras will turn us into fantastic photographers without us even reading the manuals or learning to use our cameras (thanks the the excellent @legaltwo for the hint on that one!). We think ‘porn filters’ will sort out our parenting issues. We think web-blocking of the Pirate Bay will stop people downloading music and movies illegally. We think technology provides a shortcut without dealing with the underlying issue – and without thinking of the side effects or negative consequences. It’s not true. Technology very, very rarely ‘solves’ these kinds of problems – and the suggestion that it does is the worst kind of myth.

The Snoopers’ Charter

The Draft Communications Data Bill – the Snoopers’ Charter – perpetuates this myth in the worst kind of way. ‘If only we can track everyone’s communications data, we’ll be able to stop terrorism, catch all the paedos, root out organised crime’… It’s just not true – and the consequences to everyone’s privacy, just a little side issue to those pushing the bill, would be huge, potentially catastrophic. I’ve written about it many times before – see my submission to the Joint Committee on Human Rights for the latest example – and will probably end up writing a lot more.

The big point, though, is that the very idea of the bill is based on a myth – and that myth needs to be exposed.

That’s not to say, of course, that technology can’t help – as someone who loves technology, enjoys gadgets and spends a huge amount of his time online, that would be silly. Technology, however, is an adjunct, not a substitute, to intelligent ‘real world’ solutions, and should be clever, targeted and appropriate. It should be a rapier rather than a bludgeon.

Safe…. or Savvy?

What kind of an internet do we want for our kids? And, perhaps more importantly, what kind of kids do we want to bring up?

These questions have been coming up a lot for me over the last week or so. The primary trigger has been the reemergence of the idea, seemingly backed by David Cameron (perhaps to distract us from the local elections!), of comprehensive, ‘opt-out’ porn blocking. The idea, apparently, is that ISPs would block porn by default, and that adults would have to ‘opt-out’ of the porn blocking in order to access pornographic websites. I’ve blogged on the subject before – there are lost of issues connected with it, from slippery slopes of censorship to the creation of databases of those who ‘opt-out’, akin to ‘potential sex-offender’ databases. That, though is not the subject of this blog – what I’m interested in is the whole philosophy behind it, a philosophy that I believe is fundamentally flawed.

That philosophy, it seems to me, is based on two fallacies:

- That it’s possible to make a place – even virtual ‘places’ like areas of the internet – ‘safe’; and

- That the best way to help kids is to ‘protect’ them

For me, neither of these are true – ultimately, both are actually harmful. The first idea promotes complacency – because if you believe an environment is ‘safe’, you don’t have to take care, you don’t have to equip kids with the tools that they need, you can just leave them to it and forget about it. The second idea magnifies this problem, by encouraging a form of dependency – kids will ‘expect’ everything to be safe for them, and they won’t be as creative, as critical, as analytical as they should be, first of all because their sanitised and controlled environment won’t allow it, and secondly because they’ll just get used to being wrapped in cotton wool.

Related to this is the idea, which I’ve seen discussed a number of times recently, of electronic IDs for kids, to ‘prove’ that they’re young enough to enter into these ‘safe’ areas where the kids are ‘protected’ – another laudable idea, but one fraught with problems. There’s already anecdotal evidence of the sale of ‘youth IDs’ on the black market in Belgium, to allow paedophiles access to children’s areas on the net – a kind of reverse of the more familiar sale of ‘adult’ IDs to kids wanting to buy alcohol or visit nightclubs. With the growth of databases in schools (about which I’ve also blogged) the idea that a kids electronic ID would actually guarantee that a ‘kid’ is a kid is deeply flawed. ‘Safe’ areas may easily become stalking grounds…

There’s also the question of who would run these ‘safe’ areas, and for what purpose? A lovely Disney-run ‘safe’ area that is designed to get children to buy into the idea of Disney’s movies – and to buy (or persuade their parents to buy) Disney products? Politically or religiously run ‘safe’ areas which promote, directly or indirectly, particular political or ethical standpoints? Who decides what constitutes ‘unacceptable’ material for kids?

So what do we need to do?

First of all, to disabuse ourselves of these illusions. The internet isn’t ‘safe’ – any more than anywhere in the real world is ‘safe’. Kids can have accidents, meet ‘bad’ people and so on – just as they do in the real world. Remember, too, that the whole idea of ‘stranger danger’ is fundamentally misleading – most abuse that kids receive comes from people they know, people in their family or closely connected to it.

That doesn’t mean that kids should be kept away from the internet – the opposite. The internet offers massive opportunities to kids – and they should be encouraged to use it from a young age, but to use it with intelligence, with a critical and analytical outlook. Kids are far better at this than most people seem to give them credit for – they’re much more ‘savvy’ instinctively than we often think. That ‘savvy’ approach should be encouraged and supported.

What’s more, we have to understand our roles as parents, as teachers, as adults in relation to kids – we’re there to help, and to support, and to encourage. My daughter’s just coming up to six years old, and when she wants to know things, I tell her. If she’s doing something I think is too dangerous, I tell her – and sometimes I stop her. BUT, much of the time – most of the time – I know I need to help her rather than tell her what to do. She learns things best in her own way, in her own time, through her own experience. I watch her and help her – but not all the time. I encourage her to be independent, not to take what people say as guaranteed to be true, but to criticise and judge it for herself.

I don’t always get it right – indeed, I very often get it wrong – but I do at least know that this is how it is, and I try to learn. I know she’s learning – and I know she’ll make mistakes too. She’ll also encounter some bad stuff when she starts exploring the internet for real – I don’t want to stop her encountering it – I want to equip her with the skills she needs to deal with it, and to help her through problems that arise as a result.

I want a savvy kid – not the illusion of a safe internet. Isn’t that a better way?

Doin’ it for the kids?

I was watching CBBC with my daughter this morning – waiting for the wonderful Horrible Histories to begin – when on came ‘Newsround’, the children’s news programme. On it there was a short item that sent chills down my spine: a plan (which I was later informed has already come into practice in Brazil) to put RFID chips into school uniforms, to monitor truancy and tardiness.

The idea is ‘clever’ – the chips automatically send text messages to their parents when the kids enter school or if they’re more than 20 minutes late. Given the current issues with truancy – including the recent suggestion that child benefit should be docked for persistent truants – it may well be a very attractive idea for the government and even for schools, particularly if schools are being ‘rated’ for truancy levels. And yet there’s something deeply disturbing about it – not least the way that it was reported on Newround, in a matter-of-fact way, as though this sort of thing was just a welcome and natural development of technology, without a word or hint of the ‘dark side’ of it.

When I tweeted about it, I got some immediate and very interesting responses. A number of people told me about the existing systems that require fingerprinting to get school meals – apparently one in seven schools in the UK insist on it, according to a report in the Guardian last year. That in itself is pretty chilling – and the Guardian report details many other examples of intrusive control in schools, from the ever growing number of CCTV cameras to the desire to be able to take kids phones and so forth. There are, of course, metal detectors and even armed police in some US schools, but it hasn’t come to that yet in the UK. That doesn’t mean that it won’t – or at least that similarly draconian levels of control, perhaps using more ‘civilised’ and ‘British’ methods than armed police.

Draconian control rarely ‘works’

What’s wrong with all this? Where to start…. One of my twitter responses, from the excellent @daraghobrien, predicted ‘a brisk trade in jumper swapping or storing uniform items in bags for truanting friends’, with his tongue only partly in his cheek – and there are many more equally enterprising possibilities, such as sabotaging a bit of uniform to take in any number of chips onto a single garment, allowing one person to ‘check in’ for all their mates.

Attempts at control like this rarely have the desired effect. Kids are ingenious and enterprising enough to find ways to mess with any system the grown-ups are likely to put in – which would doubtless result in further escalations, and perhaps the suggestion of another excellent privacy tweeter, @cybermatron: ‘My estimate still is that our kids will be microchipped at birth within the next 20 years. For their own protection, of course‘.

Is that where we’re headed? If we think that we can solve behavioural problems by closer monitoring and control, it’s hard not to come to that kind of conclusion. I’ve written about connected issues before (my blog a couple of months back Do you want a camera in your kid’s bedroom?? for example): there seems to be a tendency to try to use technology – and in particular privacy-intrusive technology – to try to solve problems for which it is entirely unsuited. There also seems to be a fundamental misunderstanding of kids.

Kids need freedom

Why have do so many adults seem to have forgotten what it was like to be a kid? What they liked to do when they were a kid? Kids need freedom to grow, to learn, to play. They need privacy – as a father of a five year old, I’ve already learned a lot about that. There are things that my daughter needs to keep to herself, or to talk to her friends about without her parents or her teachers knowing. We all know that, if only we think back to our own childhoods – and not just ‘bad’ things, but good things, personal things. If we go along the route of total surveillance, of attempting total control, we deny ordinary children that freedom, without even solving the problems that we want to solve!

Making surveillance and control ‘acceptable’

Perhaps just as importantly, if this kind of thing becomes the norm – and the ‘matter-of-fact’ way it was reported makes that far more likely – are we teaching kids that surveillance is acceptable? Numbing them? Chilling them? From a government perspective, if they can get kids ‘used’ to surveillance from as early as possible and there’ll be much less resistance when the government wants to bring in even more draconian measures – like the new CCDP programme of total internet surveillance currently under discussion. This is wrong in so many ways….

Can we stop it?

My daughter’s five years old – in year 1 – and hasn’t yet had to deal with any of these things. I don’t want her to have to – so if I hear anything from her school suggesting anything even slightly in this direction, I’ll be speaking out at every opportunity. We all should be – and telling all our politicians, our educators, our police, that it’s wholly unacceptable. Whether that will be enough is far from clear.

After I watched the bulletin on Newsround, I watched Horrible Histories – and wondered, not for the first time, how our period in history will be remembered in years to come. Horrible Histories has ‘Rotten Romans’, ‘Terrible Tudors’ and ‘Vile Victorians’ – and the sketches on the TV show point out the crazy, extreme and terrible things that have happened in each of those ages. How will they show the kind of thing we’re planning to do to our kids? I shudder to think…

PLEASE LOOK AT THE COMMENTS – THERE’S MORE TO READ!

Privacy, Parenting and Porn

One of the stories doing the media rounds today surrounded the latest pronouncements from the Prime Minister concerning porn on the internet. Two of my most commonly used news sources, the BBC and the Guardian, had very different takes on in. The BBC suggested that internet providers were offering parents an opportunity to block porn (and ‘opt-in’ to website blocking) while the Guardian took it exactly the other way – suggesting that users would have to opt out of the blocking – or, to be more direct, to ‘opt-in’ to being able to receive porn.

Fool that I am, I fell for the Guardian’s version of the story (as did a lot of people, from the buzz on twitter) which seems now to have been thoroughly debunked, with the main ISPs saying that the new system would make no difference, and bloggers like the excellent David Meyer of ZDNet making it clear that the BBC was a lot closer to the truth. The idea would be that parents would be given the choice as to whether to accept the filtering/blocking system, which, on the face of it, seems much more sensible.

Even so, the whole thing sets off a series of alarm bells. Why does this sort of thing seem worrying? The first angle that bothers me is the censorship one – who is it that decides what is filtered and what is not? Where do the boundaries lie? One person’s porn is another person’s art – and standards are constantly changing. Cultural and religious attitudes all come into play. Now I’m not an expert in this area – and there are plenty of people who have written and said a great deal about it, far more eloquently than me – but at the very least it appears clear that there are no universal standards, and that decisions as to what should or should not be put on ‘block lists’ need to be made very carefully, with transparency about the process and accountability from those who make the decisions. There needs to be a proper notification and appeals process – because decisions made can have a huge impact. None of that appears true about most ‘porn-blocking’ systems, including the UK’s Internet Watch Foundation, often very misleadingly portrayed as an example of how this kind of thing should be done.

The censorship side of things, however, is not the angle that interests me the most. Two others are of far more interest: the parenting angle, and the privacy angle. As a father myself, of course I want to protect my child – but children need independence and privacy, and need to learn how to protect themselves. The more we try to wrap them in cotton wool, to make their world risk-free, the less able they are to learn how to judge for themselves, and to protect themselves. If I expect technology, the prime minister, the Internet Watch Foundation to do all the work for me, not only am I abdicating responsibility as a parent but I’m denying my child the opportunity to learn and to develop. The existence of schemes like the one planned could work both ways at once: it could make parents think that their parenting job is done for them, and it could also reduce children’s chances to learn to discriminate, to decide, and to develop their moral judgment….

….but that is, of course, a very personal view. Other parents might view it very differently – what we need is some kind of balance, and, as noted above, proper transparency and accountability.

The other angle is that of privacy. Systems like this have huge potential impacts on privacy, in many different ways. One, however, is of particular concern to me. First of all, suppose the Guardian was right, and you had to ‘opt-in’ to be able to view the ‘uncensored internet’. That would create a database of people who might be considered ‘people who want to watch porn’. How long before that becomes something that can be searched when looking for potential sex offenders? If I want an uncensored internet, does that make me a potential paedophile? Now the Guardian appears to be wrong, and instead we’re going to have to opt-in to accept the filtering system – so there won’t be a list of people who want to watch porn, instead a list of people who want to block porn. It wouldn’t take much work, however, on the customer database of a participating ISP to select all those users who had the option to choose the blocking system, and didn’t take it. Again, you have a database of people who, if looked at from this perspective, want to watch porn….

Now maybe I’m overreacting, maybe I’m thinking too much about what might happen rather than what will happen – but slippery slopes and function creep are far from rare in this kind of a field. I always think of the words of Bruce Schneier, on a related subject:

“It’s bad civic hygiene to build technologies that could someday be used to facilitate a police state”

Now I’m not suggesting that this kind of thing would work like this – but the more ‘lists’ and ‘databases’ we have of people who don’t do what’s ‘expected’ of them, or what society deems ‘normal’, the more opportunities we create for potential abuse. We should be very careful…